Introduction

In 1993 we got a number of beaded items from Nigeria or Benin. Most were dirty, but brushes with water did miracles. Among other things, three items appeared to be a rider with four assistants. Gradually it became clear that this was Shopona, the god of smallpox. Here is an explanation of the West African way of dealing with smallpox and how this African knowledge came to North America and subsequent developments led to the disappearance of this terrible disease that has plagued the world for thousands of years

Shopona.

Other names: Sopona, Sopono, Sapata (Fon), Sakpata,Shakpana Shapanan. Sanponna, Ainon (Master of the Earth), Jehosu (King of beads), Obalouayé, Obaluayé, Omolou, Omolu. Alápa-dúpé, meaning “One who kills and is thanked for it”.

Also Babalu Aye (in wikipedia).

- Shopona in Africa

In the religious system of Orisha worship, Babalú-Ayé is the praise name of the spirit of the Earth and strongly associated with infectious disease, and healing. He is an Orisha, representing the Supreme God Olorun on Earth. The name Babalú-Ayé translates as “Father, Lord of the Earth” (Idowu 1962:95) and points to the authority this orisha exercises on all things earthly, including the body, wealth, and physical possessions. In West Africa, he was strongly associated with epidemics of smallpox, but in the contemporary Americas, he is more commonly thought of as the patron of leprosy, influenza, and AIDS. Although strongly associated with illness and disease, Babalú-Ayé is also the deity that cures these ailments. Both feared and loved, Babalú-Ayé is sometimes referred to as the “Wrath of the Supreme God” because he punishes people for their transgressions [=Socially harmful individuals, SR]. He demands respect and even gratitude when he claims a victim, and so people sometimes honor him with the praise name Alápa-dúpé, meaning “One who kills and is thanked for it”.

In one commonly recounted story, Shopona was old and lame. He attended a celebration at the palace of Obatala, the father of the orishas. When Shopona tried to dance, he stumbled and fell. All the other orishas laughed at him, and he in turn tried to infect them with smallpox.

His mythical lameness evokes the idea of living in a constant state of limitation and physical pain, while people appeal to him to protect them from disease.

Yoruba: an equestrian figure, sitting on a mule, with four attendants.

Beads, leather, other materials. H. 19 ¾” / 50 cm

In Art from Nigeria Hans Witte writes:

‘My guess would be Shopona, of whom Suzanne Wenger and Gert Chesi (1983) write that his priest “dresses in a camwood-red smock, his hair finely plaited. On his frock, cowrie shells and littje bells are sewn as a warning of the dangerous god’s arrival. Shopona is the god of contagious disease, especially smallpox, whose name is so dreaded that it is not spoken. Instaed, he is euphemistically refered to as King of the World, Owner of the Hot Water, Lord of the Open, and also King of Pearls (Idowu, 1962:95-101; Geaffrey Parrinder, 1969:55; Una McLean, 1971:38). The cult of Shopona has been prohibited by the British colonial authorities and by the Nigerian Government because it was supposed to spread contagious deseases. As a result, an air of sevrecy has grown up around the cult.’

The bells are attached to the coats of the figures (mule?) Figures. The cloak over the back of the rider also hangs bubbles. There are still relatively big bubbles around the body. Many caurie shells are attached to the assistants’ jaws. Shopona is also affiliated with cauries and trade

Verger (1981-82): Obalouayé-Shapanan had led his warriors in expedition to the four corners of the earth. A wound from their arrows made people blind, deaf or lame.

All comparable groups have four assistents.

Figures on a box (?), Schaedler (1994)

The asé (Yoruba: the power to make things happen and produce change) of Obalouayé Is brought by a woman in a state of trance: she walks with hesitant and staggering steps, followed by carriers of gourds containing foods. For all three groups there are carriers of gourds or urns. This quote could give a statement, but mention is also made of Sopona, the king of beads, who measures his beads in vessels.

Verger also reports that Shopona, or more cautiously referred to as Obalouayé or Omolou, has been taken by the slave trade to the Caribbean and Brazil. The followers carry two kinds of colliers: the lagidiba, made of small black discs, and another type of brown, black striped glass beads. All rider figures carry (many) strings made with black discs and some assistants wear them as well.

- Shopona and the slave trade The slaves made Africans went to America with Shopona and other half-gods. Here too, all kinds of euphemisms are used to not mention his name. He is being synchronized (fused) with Saint Lazarus or with Saint Roque in Bahia, Brazil and Cuba. With Saint Sebastian in Recife. There are special variants of the original cult, which already had different variations in Benin (Dahomey) and Nigeria. There were regulations regarding the food of followers, and ritual and ritual objects were developed. When boarding Africans slavish, they saw that many wore special scars on their arms. Its meaning was not clear.

Advertisement for runaway slaves in Virginia:

‘Who will deliver the said negro to me, or secure her in any jail so that I get her again shall receive the above reward.

N.B This woman has some remarkable scars on her arms, resembling burns.’

In the “new world”, among these populations, frequent epidemics, including the dreaded bullying that often and many victims demanded. It came to the conclusion that the slaves who carried these strange scars were not susceptible to smallpox. They were therefore worth more money.

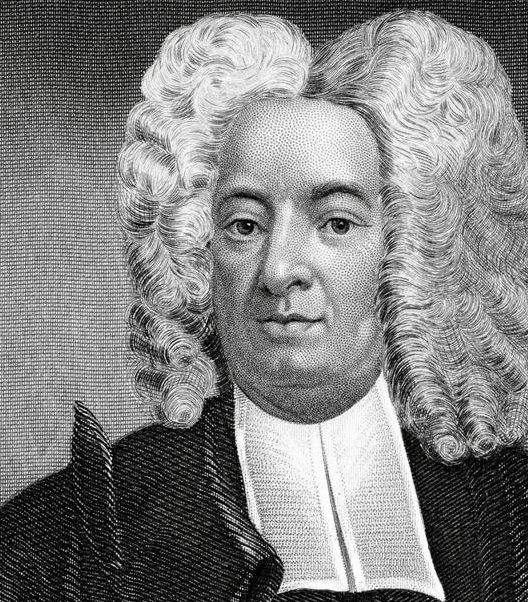

3 Variation, vaccination and vaccination The name of the African pox prevention in North America has been known. The famous Puritan preacher Cotton Mather taught the technique of vaccination of an African slave he had, Onesimus. He wrote to his friends: ‘… the treatment of the smallpox, with the inoculation method. I had it from my own servant, my negro-man Onesimus. He described the operation to me and gave me his arm, the scar that he had left him. It was often used under the Guramantese. ‘

Cotton Mather

‘I have since met a significant number of these Africans, who all agree in one story. People Take Juice or Small Pox … then through and through a bit sick, sickly, there are few little things like little pox and there are none of it and there are no small pox anymore.’

Mather launched a public campaign, and Boylston inaugurated his son and two slaves. All three developed mild infections, making them immune. Their efforts were met with great opposition.

Mather: I Never Seen The Devil A guiding mind had gone out of such a pace that nothing was heard what ever heard. If the inoculated patients were a little sick, or had they given a Vomit, they were immediately told to be dead or even dead. . . But never had a patient so much puzzles from the little poxy, because Lies was told daily and spread among our deceived people.

Mather encountered by recalling his critics to the proven value of indigenous medical knowledge: “I do not know why it is unlawful to learn from Africans, how to help the Poison of the Small Pox than it is necessary to learn from our Indians, How To help with the rattlesnake poison. ‘

Boylston allegedly had to hide in his own house for two weeks, at one point, “while parties came in search of him day and night.” Others threaten to hang him. In November, a homemade grenade was thrown into Cotton Mather’s house, but did not appear to explode. An attached note reads, “Cotton Mather, your dog. Damn you! 111 Put your pox in here”.

During an outbreak in Boston 270 people were inoculated. Six of them died. Of the 5980 others died 844. Evidence that inoculation saved lives led to its general acceptance. However, in the hands of the medical elite it became an expensive treatment.

The evidence that inoculation preserved lives led to its general acceptance as a legitimate medical procedure. In the hands of the medical elite, however, it became an expensive treatment that only the well-to-do could afford.

Besides, slave dealers began routinely inoculating their chattels as a means of maximizing profits. Because immunized slaves were considered a safer investment, they brought a higher price.

Immunization was extended to the working class in 1777 to 1778 when George Washington had the soldiers of the Continental Army inoculated in ´the first largescale state-sponsored immunization campaign in American history. Washington knew that the Britisch wanted to put pox on their army. Before, the British had eradicated large numbers of Indians by handing out infected blankets with this disease.

Historians say that Washington´s decision was essential to the victory of the American Revolution. To the extend that is true, the United States owes its very existence to the medical knowledge transmitted by Onesimus and other Africans.

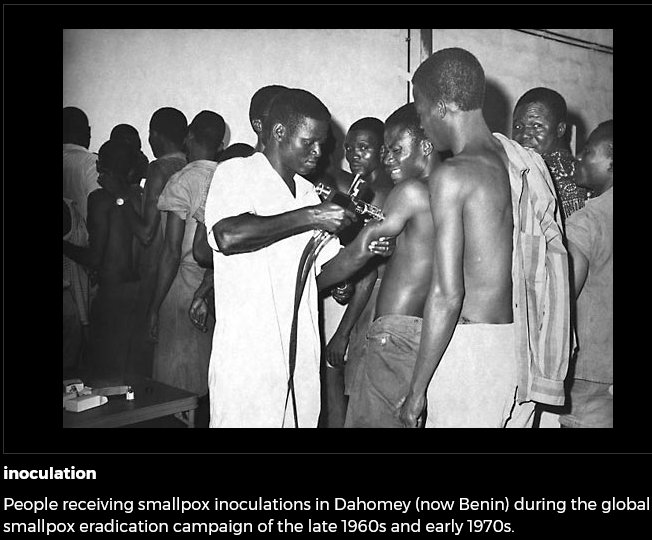

Jennerian vaccination was first practiced in Cape Town, before the epidemic of 1812. As the 20th century progressed, improvements in vaccination and vaccine made control increasingly effective, but was sensitive to heat and many Africans were not successfully protected. The French developed a vaccine better suited to tropical climates. Nevertheless, the older type of glycerinated vaccine lymp was still used widely in West Africa into the late 1960s. Smallpox was responsible for an estimated 300–500 million deaths during the 20th century.

In Nigeria, Dahomey (Republic of Benin) and Togo the Earth God Shapona was present and his priests inoculated people. Although Shapona was banned in Nigeria in 1907, a struggle was going on between colonial doctors and traditional healers. It was an ideological, (post-) colonial and medical struggle who went on.

Small pox was very dangerous until not long ago. As recently as 1967, theWorld Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 15 million people contracted the disease and that two million died in that year.

The WHO certified the global eradication of smallpox in 1980.

Literature:

Encyclopaedia Britannica: Inoculation. www.britannica.com/science

Hopkins, Donald R. The greatest killer, Smallpox in History. Un. of Chicago Press, 2002

Schaedler, Karl-Ferdinand: Lexicon afrikanische Kunst und Kultur.Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1994.

Verger, Pierre Fatumbi: Orisha. Les dieuxYorouba en Afrique et ou nouveau monde. Ed. A.M. Métailié, Paris 1982.

Waldstreicher, David. Runaway America: Benjamin Franklin, Slavery, and the American Revolution. Douglas & McIntyre, 2004

Widmer, Ted: How an African slave helped Boston fight smallpox. The Boston Globe, 19 October 2014

Witte, Hans: Art from Nigeria. Gallery Kathy van der Pas & Steven van de Raadt, Rotterdam 1994.