INTRODUCTION

Today, people who engage in African art are at least aware of the fact that we are not dealing with a-historical cultures in which one mechanically continues to copy a number of forms, but that (just) in Africa cultures are open to changes.

As regards many areas, one sees the process of taking over successful elements of other cultures, whether or not combined with the artistic expressions that relate to it.

The many migratory flows in Africa also contributed to this. We also often see the phenomenon that winner and loser assimilate after an area conquest.

These influences from outside Africa have long been a factor. Especially the east coast of Africa has been known for several millennia of Arab and Asian influences.

The following article deals with European influences in southern Africa.

NEW MATERIALS, NEW POSSIBILITIES

In this area of culture, the production of masks and figures has hardly played a part. On a large scale, one has kept busy and is still focusing on what is described today as ethnic design. This distinction between art and design is certainly hard to make in southern Africa. Under difficult circumstances, inventive and artistic produced very remarkable objects were produced. However, they all have one thing in common: they can also be used as an usable object or item of clothing.

What we can also find often is that the manufacturer makes items for personal use, but also for the neighbors and to sell at the door to whites or to along coming tourists if that is possible. Such a far-reaching flexibility we find in the rest of Africa especially in pottery production.

To the extent that we have objects available for study and comparison, we can find that the design in this area is relatively quick to change. The turbulent history of the area and especially the moved history from the Dutch Colony’s foundation in 1652 will have caused that too.

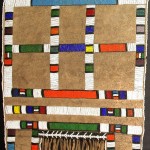

The Dutch farmers also brought cufflinks made of mother of pearl. The first were defeated on the battlefields. They inspired the manufacture of all kinds of items in the southern Nguni area. The Mfengu Iqhiya Shawls are completely built up by these cufflinks.1)

The English also contributed a commendable object: the copper uniform knot. Since these knots were first collected on the battlefields, a cord that was completely manufactured was a very high military distinction. The knot was incorporated into all kinds of objects, especially in the northern Nguni area.2)

From the middle of the 16th century, increasing amounts of beads were imported through the Delagao bay.

Long before the arrival of Europeans there was an interest in beads. Large amounts of beads from the 8th-9th century are found on the southern edge of the Kalahari.

For a long time, the kings in this area managed to maintain a monopoly on trade in these beads.

It is remarkable that, as far as we can check, only the Sangoma, the healers, were interested in the artificial beads from Murano (Venice). The monochrome bead was used in all kinds of color combinations within the material culture of almost all peoples in the area. By using (strings of) beads with consecutive colors one could even send messages. Symbols were also formed with beads.

Both possibilities were used in the so-called love letters.3)

It was common practice to deduce from a given color scheme in a certain period. These modes make it possible to date a lot of beadwork quite accurately. The cultures in southern Africa were soaked with bead art.

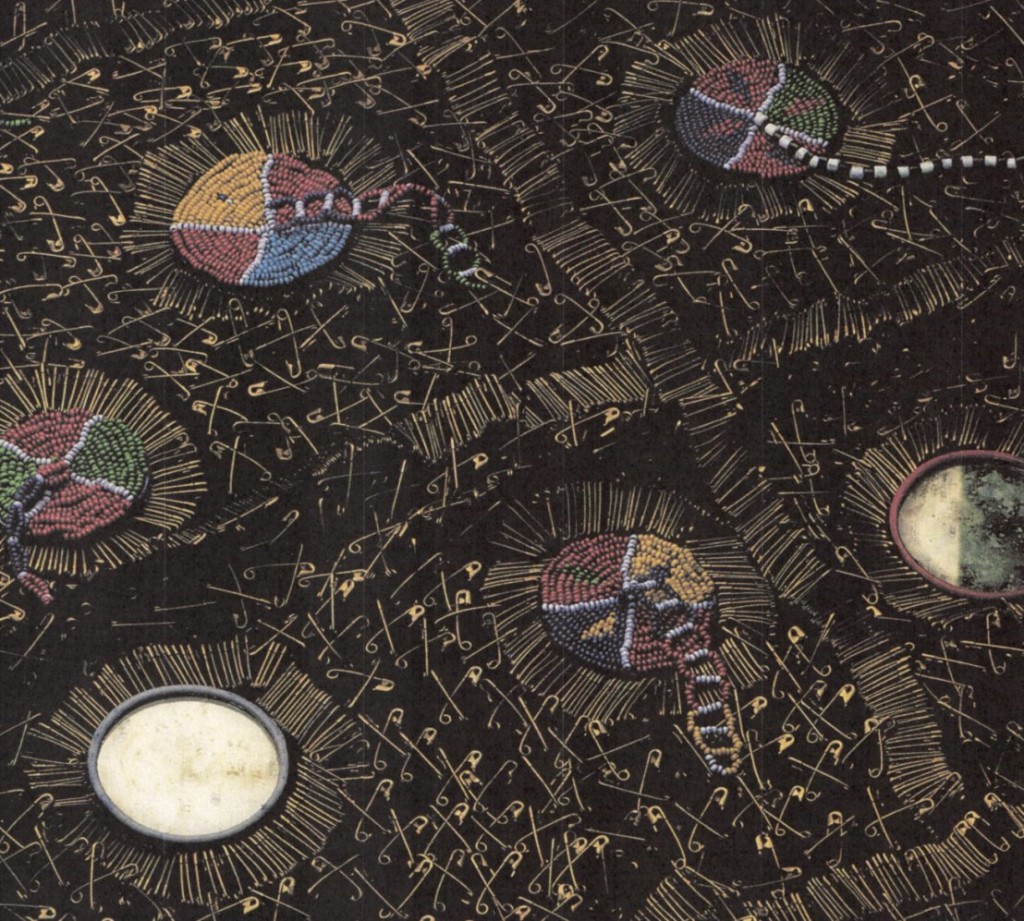

Slots and keys were of course nice to handle as decorative and symbolic objects. The security pin became a favorite object. After using these years, inter alia as ‘closing’ or affirmative symbol within the visual language, Tsonga-Shangana artists came up with the idea that Nceka shoulder wraps were based primarily on safety pins.

Autumn 1994, such a canvas was on the cover of the African Arts magazine.4) They also use mirrors in the compositions. This edition also shows a Lovedu apron in which plastic beads and wristwatches are processed and four Tsonga-Shangana hipbands in which brass bells, rings and coins are processed.

In many publications one can see the development of the Ndebele aprons.5) In some early copies (manufactured around 1900) a mirror was further processed. Until the 60’s they consisted of beads and leather.

Then they are going to manufacture the Plastici on a large scale.6) Felt colors plastic, tape and lace strips were used. However, for export they were not suitable. Collectors regarded them as ‘non-authentic’. It is to be feared that only a few compositions of plastic beads will also penetrate the western world.

Thankfully the last few decades a lot of use is made of the colorful possibilities of telephone wire. Many peoples in southern Africa have been using highly developed braiding techniques for centuries. Natural fibers and color variations in metal wire were used.7)

Telephone wire offered a number of artists new possibilities. Scepters are wrapped around with it, all kinds of varied braided baskets are manufactured and in recent years they also make figurative images.

In South Africa, a lot of irritation arose because this wire was pulled from illegally excavated cables.8) It is not so far that, in order to support such an interesting development the government, for instance, makes these things available.

OTHER EUROPEAN STIMULANS

A European object, which is included as such in South African cultures, is the pipe.

One starts to imitate the German Ulm pipe and the Dutch Gouda pipe in various materials. This was the starting point of a development in which a wide variety of forms arose. In addition, metal was used for inlaid patterns or pipes were ornamented with beads in whole or in part. Also figurative elements are added.

We also see that in the form of the pipe, the spoon, the neck rest or the staff, a pistol, a gun, a car wheel, a locomotive or a horse rider is integrated. The variations seem to be endless.

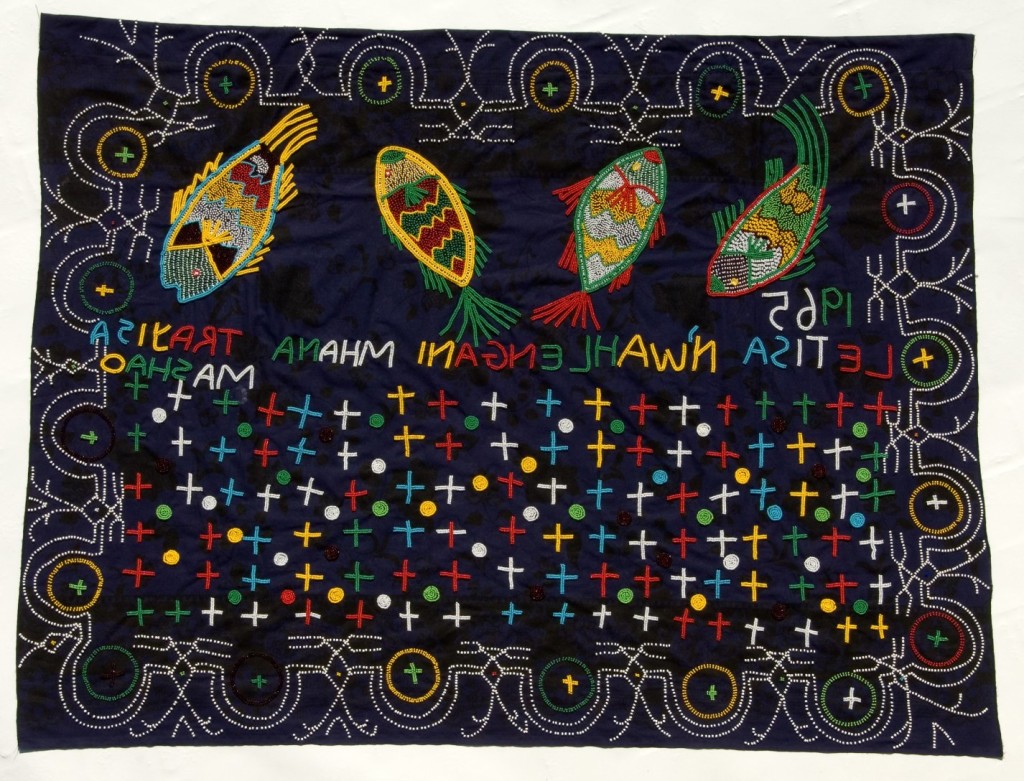

The alphabet is also a source of inspiration. Sometimes, only the graphical qualities are used, as with the Ampasi Necklaces from KwaLatha since the 60’s.9) Other times there is also a literal meaning.

Often, the individuals or small groups of artists who hit new roads, as we have seen with the security pins (some makers are known) and the telephone wire arts. The makers confirm their name, written on cardboard, but unfortunately they are almost always lost.

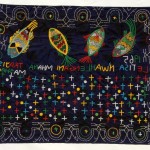

A beautiful example are the Tsonga wraps. In the 1960’s, women were producing machined fabrics with beautiful performances made with beads. Some of them are dated and signed.10) When they were known outside the region and researchers hit the road it was too late: the creators had disappeared .

Twenty-five years ago, a new art form emerged when a group of rural women, who previously made curio beads for sale. By accident, they entered an art gallery in Johannesburg. They were astonished at these creations. At home they began to make all kinds of (groups of) figures and from beads and modern fabrics. Sizakhele Mchunu and others soon attracted the attention of the international art world with their artwork.

This can not be said about the Western (Barbie) dolls that Ndebele women and others provide with traditional beaded dresses.These moving objects almost did not generate any interest. Here we present a Kewpie doll adopted by the Hakaoma people in Angola:11)

CONCLUSION

From the foregoing it will be clear that it is impossible to memorize all developments in which artists in southern Africa have used innovative materials of European materials or other cultural elements.

It has become clear that in this part of Africa Sfricans have gone through a very vital way of artistic developments. In many areas and within many cultures, (groups of) individuals have seen new possibilities. From their tradition, they saw new ways for their creativity.

There is every reason to assume that in the near future, we will often be surprised by new forms of material culture by the hand of mostly autodidactic artists.12)

Images:

- 1. Iqhiya shawl, Mfengu. . Composition with cufflinks. Length about 100 cm. 1950s. Exhibited: Kunsthal Rotterdam ‘Vormen van verandering’ December 19, 1998 – April 25, 1999. Provenance: Privat collection? Galerie Kathy van der Pas & Steven van de Raadt?

2. Nguni belt. , glassbeads, metal buttons. L.. 75 cm, B 6 cm

Provenance: Galerie Kathy van der Pas & Steven van de Raadt. KwaMuhle Museum, Durban.

Exhibited: Oberösterreichischen Landesmuseum Linz ‘Spuren des Regenbogens – Leben im südlichen Afrika’ April 2 – November 4, 2001

Published: Stefan Eisenhofer (Ed.) Spuren des Regenbogens / Tracing the Rainbow. Linz 2001 fig. 97

3. Xhosa necklace, ‘love-letter’ iphoco. 3 glassbead panels fro 6 x 6 cm. 1930’s. Probably Mpondomise tribe.

Galerie Kathy van der Pas & Steven van de Raadt

4. Detail of shoulder wrap (nceka). Tsonga/Shangaan. Cloth, mirrors, beads, brass safety pins. L 148 cm

Provenance: University Art Galleries, Johannesburg (The Standard Bank Collection)

Published: African Arts, autumn 1994 Vol.27 No.4

5. Ndebele apron amaphoto. Leather and glassbeads. 61 x 45 cm

Provenance: Galerie Kathy van der Pas & Steven van de Raadt

Exhibited: Kunsthal Rotterdam ‘Vormen van verandering’ December 19, 1998 – April 25, 1999.

6. Ndebele plastici: apron tshogholo. Plastic. Plm. 60 x 45 cm

Provenance: Museon, The Hague

Exhibited: Kunsthal Rotterdam ‘Vormen van verandering’ December 19, 1998 – April 25, 1999.

7. Two telephone wire baskets. Metal wire. H 9 cm, D 18 cm

Provenance: Galerie Kathy van der Pas & Steven van de Raadt

Exhibited: Oberösterreichischen Landesmuseum Linz ‘Spuren des Regenbogens – Leben im südlichen Afrika’ April 2 – November 4, 2001.

Published: Stefan Eisenhofer (Ed.) Spuren des Regenbogens / Tracing the Rainbow. Linz 2001 fig. 81. Kunsthal Rotterdam ‘Vormen van verandering’ December 19, 1998 – April 25, 1999.

8. Telephone wire basket. Telephone wire. H. 7.5 cm, D. 24.5 cm

Provenance: Galerie Kathy van der Pas & Steven van de Raadt

Exhibited: Oberösterreichischen Landesmuseum Linz ‘Spuren des Regenbogens – Leben im südlichen Afrika’ April 2 – November 4, 2001.Kunsthal Rotterdam ‘Vormen van verandering’ December 19, 1998 – April 25, 1999 .

Published: Stefan Eisenhofer (Ed.) Spuren des Regenbogens / Tracing the Rainbow. Linz 2001. fig. 56

9. Ampasi necklace from Kwaletha. 1960s.

Provenance: Galerie Kathy van der Pas & Steven van de Raadt

10. Tsonga / Shangaan shoulderwrap. Cloth, glassbeads. 111 x 150 cm. 1960’s

10. Tsonga / Shangaan shoulderwrap. Cloth, glassbeads. 111 x 150 cm. 1960’s

Provenance: Galerie Kathy van der Pas & Steven van de Raadt

Exhibited: Oberösterreichischen Landesmuseum Linz ‘Spuren des Regenbogens – Leben im südlichen Afrika’ April 2 – November 4, 2001

Published: Stefan Eisenhofer (Ed.) Spuren des Regenbogens / Tracing the Rainbow. Linz 2001 fig. 72

11 American Kewpie puppet edited by Hakaone people, Angola. H. 22.5 cm

Provenance: Galerie Kathy van de Pas & Steven van de Raadt

12 Necklace, Cape Town 2016. Zippers of vislon plastic resin. D 18 cm

Provenance: Galerie Kathy van der Pas & Steven van de Raadt